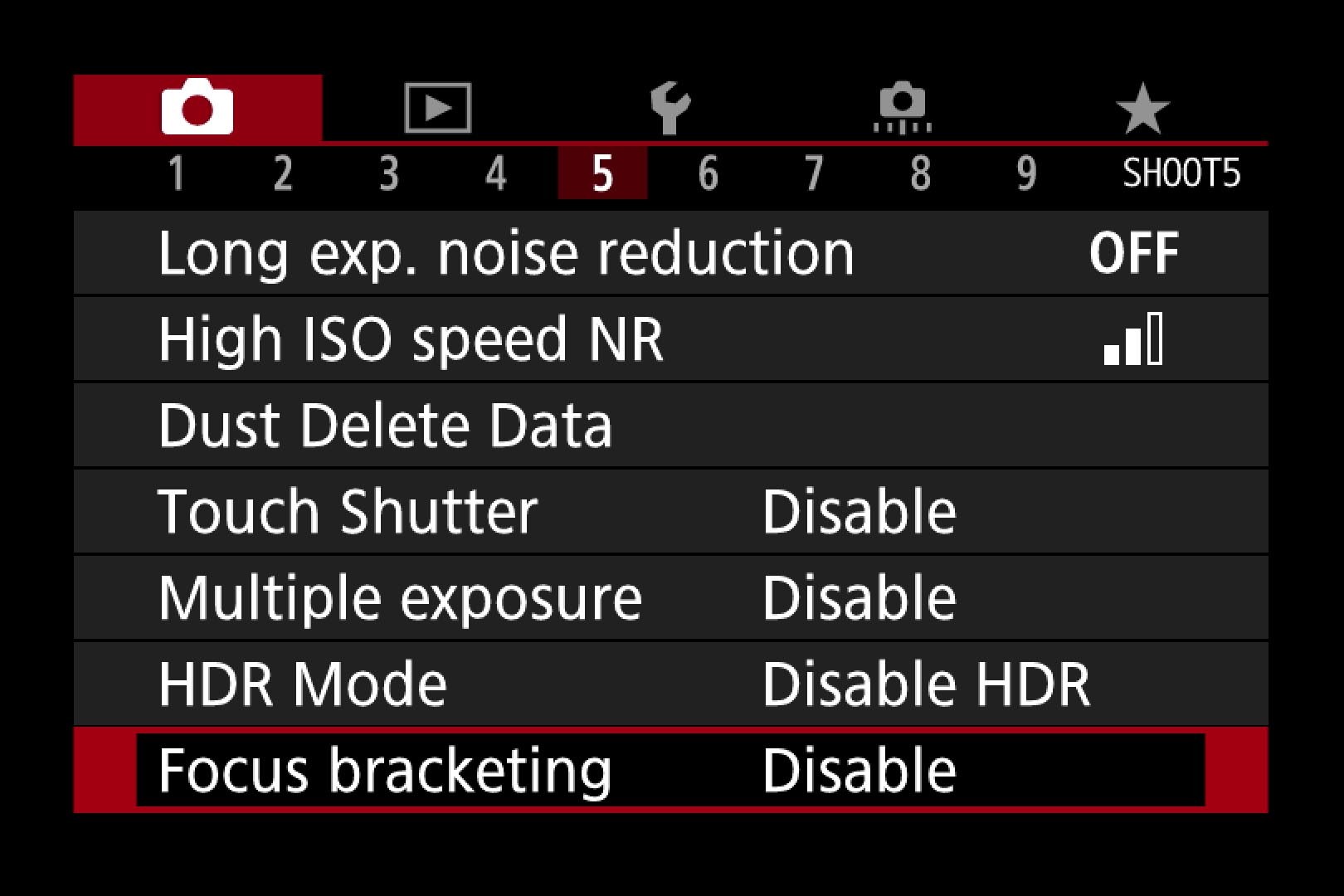

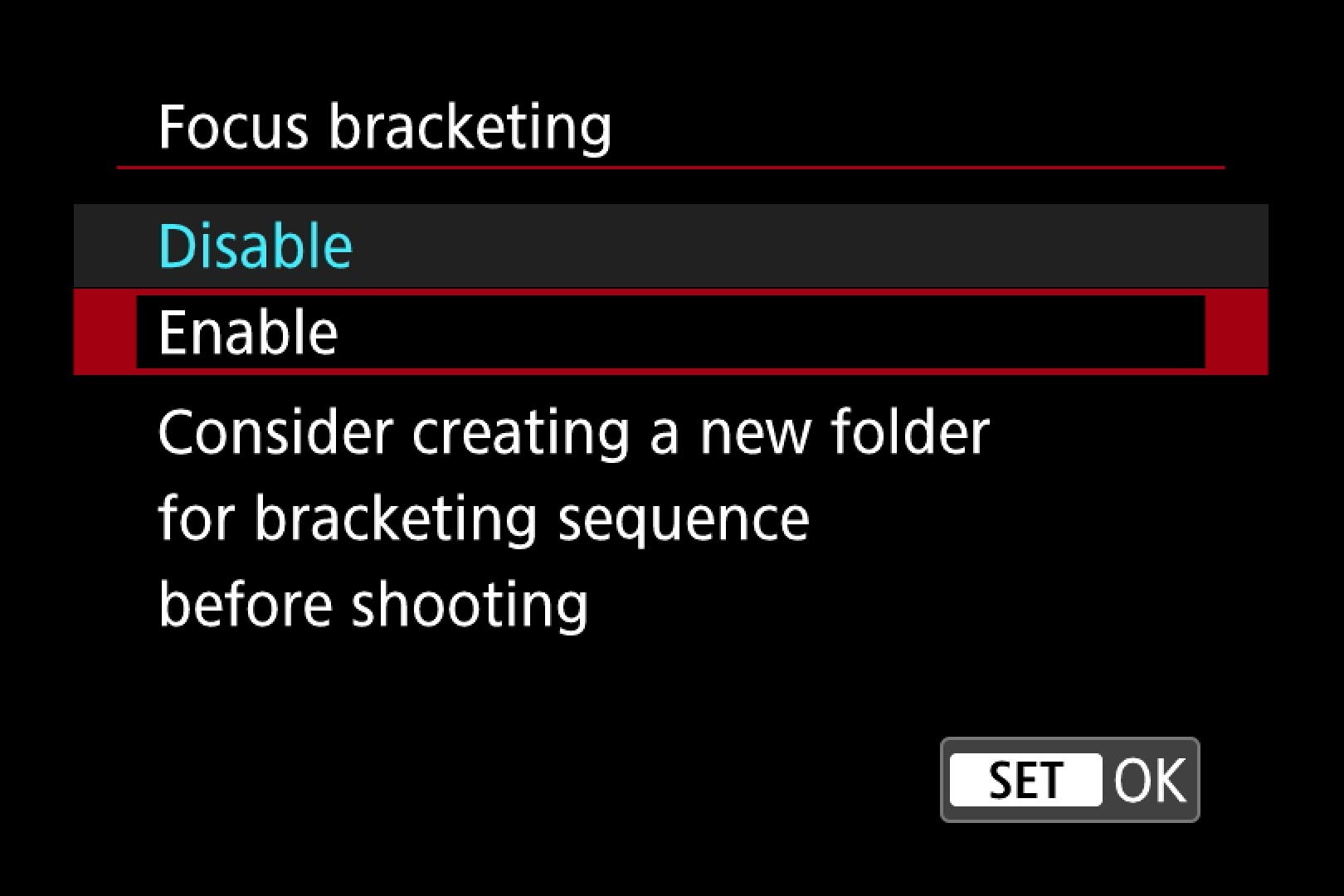

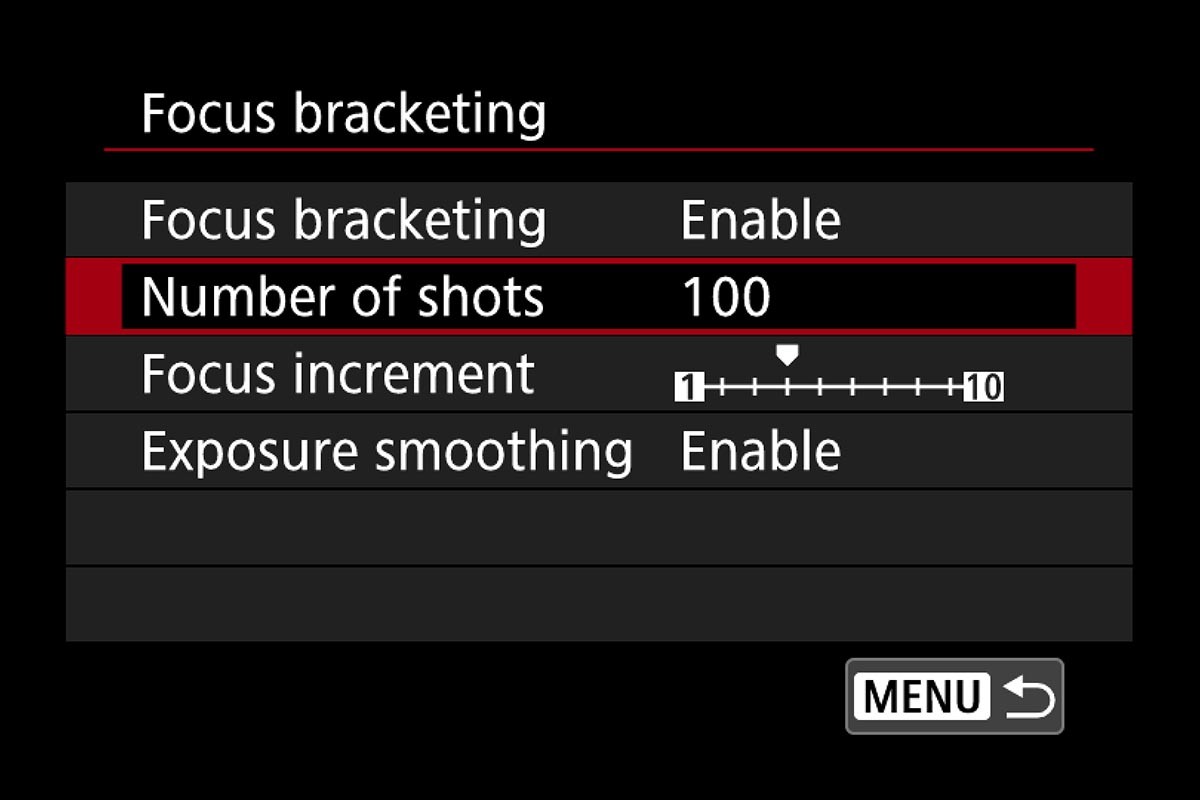

The closer you get to a subject, the smaller the depth of field becomes. Even when stopping down to 16 or 22, the depth of field is limited in macro shots. With a so-called "focus stack", you can extend the depth of field almost indefinitely. The key to this is the focus bracketing function.

The factors that influence the depth of field are the aperture, the focal length of the lens, the shooting distance and the sensor size. In the close-up and macro range, the magnification replaces the shooting distance as the limiting factor. As a rule of thumb, you can say that the depth of field decreases disproportionately when you get into the close-up and macro range. As a rule, a reproduction scale of 1:2 is referred to as the close-up range and when it approaches 1:1 and beyond as the macro range. 1:1 means that the object to be photographed is exactly the same size on the image sensor as it is in reality. The depth of field then becomes extremely shallow, no matter how wide you stop down.

Tip: you should only stop down the lens beyond f/16 in exceptional cases. Above this aperture, so-called diffraction blur, a physical imaging error, occurs with almost all lenses. The entire image then becomes slightly blurred.

The solution for the close-up and macro range

In order to achieve a depth of field that goes beyond the photographic-technical, especially when photographing very small objects, you can use a mixture of shooting and image processing.

To do this, you take a series of pictures of the same subject. These shots must all be congruent and therefore only work from a tripod and with static objects, for example a piece of jewellery or a small model or other small objects. Each shot covers an area of the subject in focus and these are then combined with software to create a single shot that is sharp from front to back. This makes it possible to create any depth of field, not only over the entire object, but also over just a part of it if desired.